Learning has always been an ambivalent topic for me. In school, it was cumbersome, and I didn’t find much joy in it. On the other hand, I’ve always enjoyed picking up new skills that interest me, like juggling or card magic. While I’ve never deeply developed any particular skill, I’ve become better at learning autonomously.

This autonomy helped me later in life, especially when I did a career switch from physics to software/data engineering three years ago. While I was skilled enough to land a job, I lacked knowledge in several areas and felt behind with a lot of ground to cover. My old, intuitive way of learning had worked before, but it felt inefficient and unsatisfactory. I didn't feel in control of the things I learned, and I reacted more to the things I randomly encountered rather than following a structure. Also, nothing really seemed to stick for long. I often had to relearn things, which felt more like starting from scratch rather than building on the past.

As I believe that learning is one of the most important skills in life, especially in areas that change quickly like software engineering, I decided to try to get better at it. I have read, viewed and studied some resources and tried various approaches and refined the ones that worked best for me. In the following, I present some of my key findings that I believe have been the most important in improving my way of learning. Note that all of this is non-scientific, highly opinionated and just a snapshot of my current thinking.

You will forget things, get used to it

Our brain is not meant for endless storing and exact retrieval of knowledge[^1]. Accept this. We will all forget things we previously spent a lot of time to learn and understand.

For me this always felt disappointing, like losing something valuable, so why even acquire it? Also learning something new always has this feeling that I would need to forget something old. The key to solving this dilemma for me was to first change my view on learning. Instead of seeing the goal of learning in being able to remember facts, I shifted to enjoying the process of changing the way I think. So even though I know that I will not be able to remember all of it in the future, I know that new connections have formed in my brain that may make it easier for me to pick up something similar.

Second I implemented a knowledge management system, where I write atomic notes on the things I learn. These atomic notes are like short summaries of concepts or fractions of concepts that are small enough to view and quickly grasp in isolation, even though they may be part of something far bigger. They act like checkpoints in a video game and allow me to pause studying a topic and come back to it later. So even when I will forget things it does not feel like I lost something, as I can easily retrieve it by reading my own thoughts. After all, who could better teach you a topic than yourself? This allows me to forget and lowers the pressure of keeping everything in my brain.

In a sense I have used such knowledge management systems, or like some call it second brains, unconsciously in the past. Like remembering only where in a book or website specific things are written instead of remembering them myself. So building and using such a system consciously for learning and separating it from external resources just made sense.

Another great thing about writing about the things you learn is that you are actually forced to actively engage with the topics you are studying. You stop from being a passive consumer and already become a creator just by recapitulating things in your own words or consolidating multiple sources. This idea is so important that it will pop up multiple times throughout this blog.

To build your own knowledge management system, I would recommend starting as small as possible and getting things going. There are endless tools and frameworks out there with varying complexity, just choose something that looks fine; you will not get it perfect the first time you try anyway. Stick with it and refine it as you go. You will notice things that work for you and things that bring you no value. Feel free to drop things that bring you no value, and don't get fixated on doing it the 'right' way. Building a knowledge management system is very personal, so your way will quickly diverge from postulated systems from experts.

The only thing I would say that is a must have for such a system is that you can trust it. As you will put a lot of time and value in it, the things you write should be secure. I would recommend first implementing a backup strategy for your system that you can trust. Then you can fully engage with it without a worry. (But other people have far higher requirements for the system they use see this blog post.

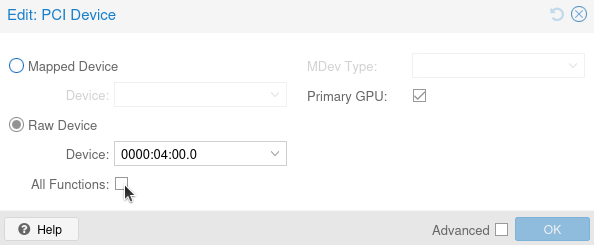

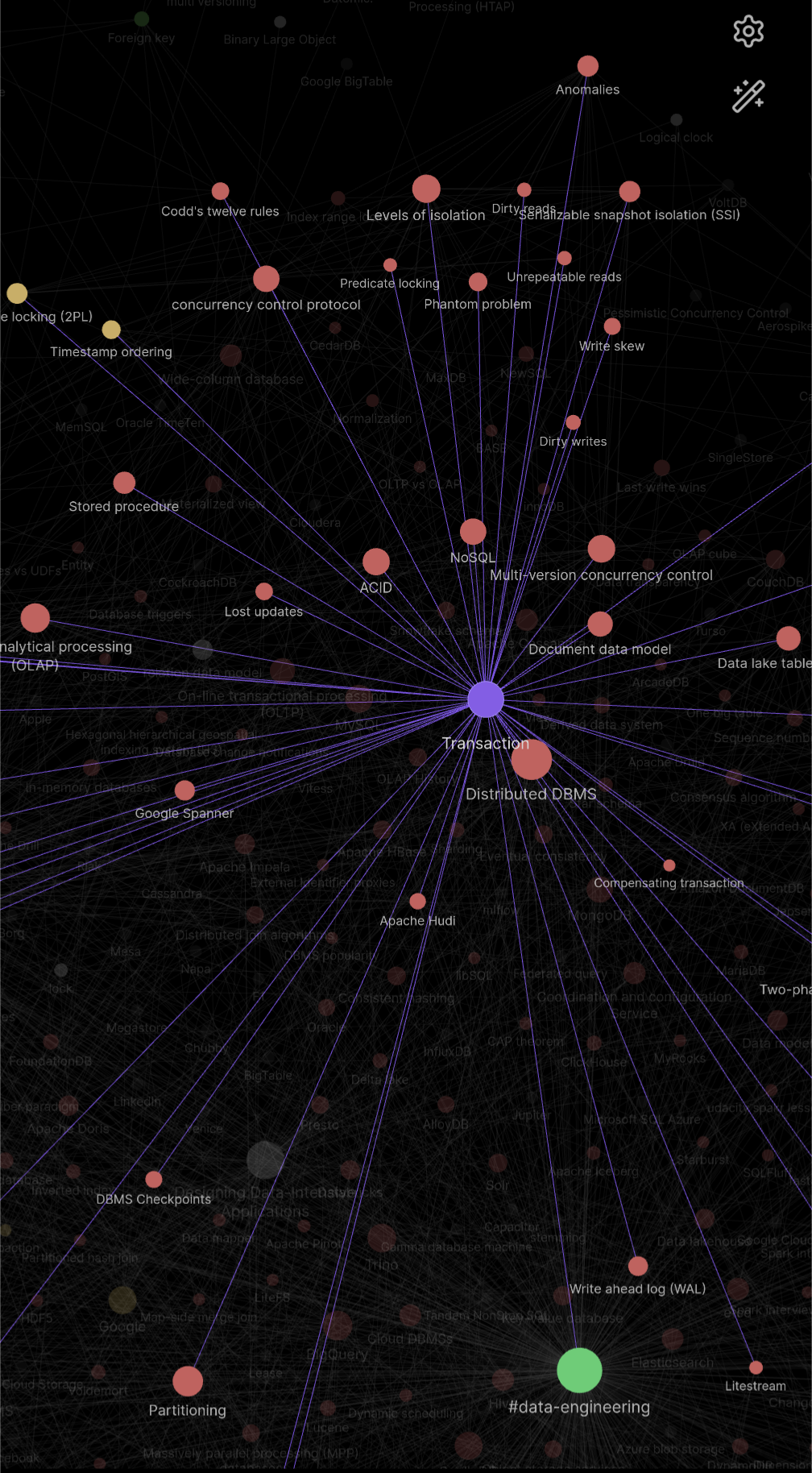

For my system I mainly use markdown files that I edit with neovim. I sync those files with my phone using Syncthing, as it is very important to me to also have access to my notes when I am not at home. On my phone I use the Obsidian app, which in the end is just a nice (but extremely powerful) wrapper around markdown files. For example it allows to reference other notes, creating connections between, which can be very helpful to navigate older notes and put things in perspective. As I am using Obsidian I also use this vim plugin. To trust my system and make it durable I make daily automated backups to an external harddrive and my Google drive using rclone. With this, I have relatively recent versions of my notes on four devices at all times.

Here is a graph view in the Obsidian app of some of my notes and how they connect with each other:

Learning is effort and is not supposed to be easy

Learning differs significantly from merely being presented with knowledge. Learning is exhausting and often not pleasant. It involves being challenged and getting frustrated. If something is too pleasant, you should question whether your are actually learning or just consuming.

When I noticed this the first time I felt discouraged, because my natural instinct is to avoid uncomfortable situations. Feeling frustrated when learning something new made me think that I was doing something wrong and I rather questioned if I was on the right track. Perhaps I was indeed doing something wrong by challenging myself too hard and should have chosen a different approach. On the other hand, simply doing things that come easily to oneself will not lead to actual growth. What remains is a small sweet spot area where you feel slightly uncomfortable and may sometimes get frustrated, but you are not too far away from your area of competency to easily get discouraged. Finding this area is not easy but being sure that it exists, no matter where you are coming from, helps.

For me one example of this was when I was working through the book "The Algorithm Design Manual" by Steven S. Skiena and tried my luck on the suggested leet code challenge as an exercise in one of the early chapters. I quickly got stuck on a challenge that required a Fenwick tree, a rather advanced data structure, that was just too hard to grasp at my current level of understanding. Even though I pushed through with the help of external resources, it took me an enormous amount of time and I thought about just not doing these challenges anymore for the following chapters.

But instead I just acknowledged that some of the suggested challenges were too hard for me at the time and took a step back. I sought out related easier challenges first before tackling the suggested ones. And started to systematically work through learning paths of easier concept like LeetCode 75 , to gradually train my problem solving. While this made my progress feel slower as I had to work through more stuff, it made it far more enjoyable and helped me build up momentum.

On another note, I have become more aware of the big difference between simply consuming knowledge and actual learning by engaging with it. It may sound like a foolish thing, but I simply asked myself: "With deep knowledge on all niche topics available at our finger tips. May it be through classic books, YouTube tutorials or generated by some large language model. What stops anyone from becoming an expert by just consuming the essentials as fast as possible?" It just felt like a straightforward path that anyone with enough time on their hands could achieve.

But personally I noticed that just consuming excellent work, does not lead to excellent understanding. With recommendation algorithms suggesting all kind of content, I have consumed videos that delve into in-depth art analyses, historical events or workings of the economy. And while these videos were well structured and covered topics exhaustively I don't feel knowledgeable about any of these topics. I may have come across a new idea or concept that felt new and exciting while watching, but actually retrieving this information to explain it to someone else or putting it in context with other things, felt impossible. The only things that stuck with me are out of context fun facts. (Which is still neat.)

The key difference between consuming knowledge and truly learning is the act of actively engaging with new information. Even if a concept is presented to you in organized and bite-sized portions, you must make the effort to "re-invent" it yourself.

- You have to care about the problem it solves, because, after all, why should you understand it if it brings you no value.

- You have to understand how it relates to the bigger picture. Concepts do not exist in a vacuum, they are always connected. Finding these connections makes them easier to remember and accelerates learning new ones as you can leverage your existing understanding.

- You have to challenge your understanding of it. Explain it to yourself or others without using the original source. Look for weak points. Maybe you find out your understanding was incorrect and needs adjustment.

- You need to use it. Actually using new knowledge can feel so rewarding. Additionally, by using it you will be forced to go through the above steps.

I first encountered these ideas in an excellent YouTube video, which I highly recommen—and ultimately summarized parts of it to deepen my understanding.

To enforce parts of this in my learning routine I use a popular system, which brings me to my next topic.

Use spaced repetition with effortful retrieval

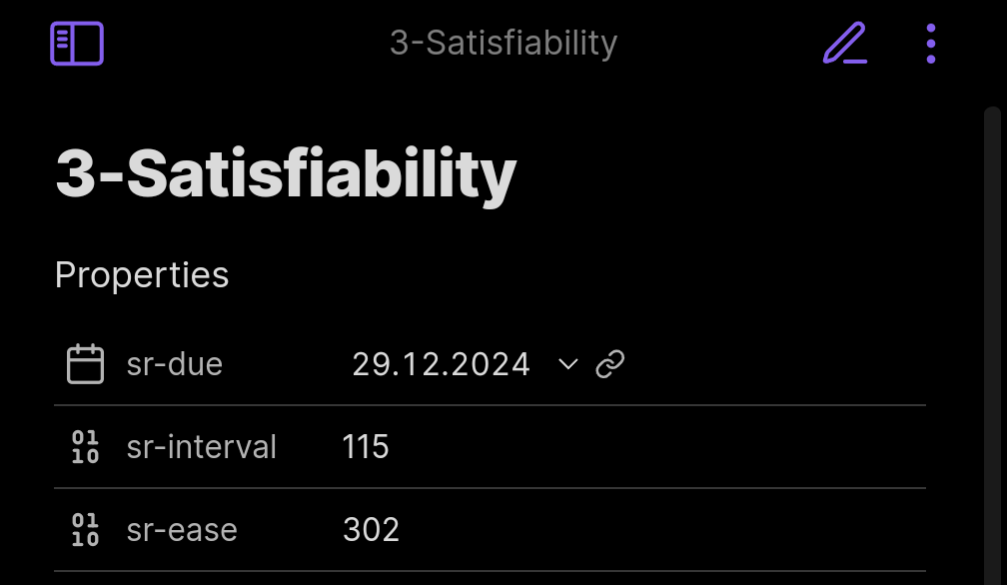

Spaced repetition is the process of repeating learning exercises in intervals that adjust based on your performance. In practice this means that you repeat a learning exercises more often when it is new to you and the better you get at it the less frequent you repeat it. The goal here is to repeat an exercise when you begin to forget about it, refreshing the connections in your brain. You may be familiar with this approach for learning vocabulary and there exist many tools to easily implement it. I use Obsidian Spaced Repetition.

Spaced repetition works great in combination with my personal knowledge management system. Here I treat the effortful retrieval of a note as a learning exercise. In practice this means that I try to recapitulate the gist of a note to myself, figuring out how I would explain the concept to someone unfamiliar with it. This forces me to actively engage with the knowledge, always re-inventing it as described in the previous section.

In action this looks like this:

Each note I want to review using spaced repetition is assigned a due date for its next review.

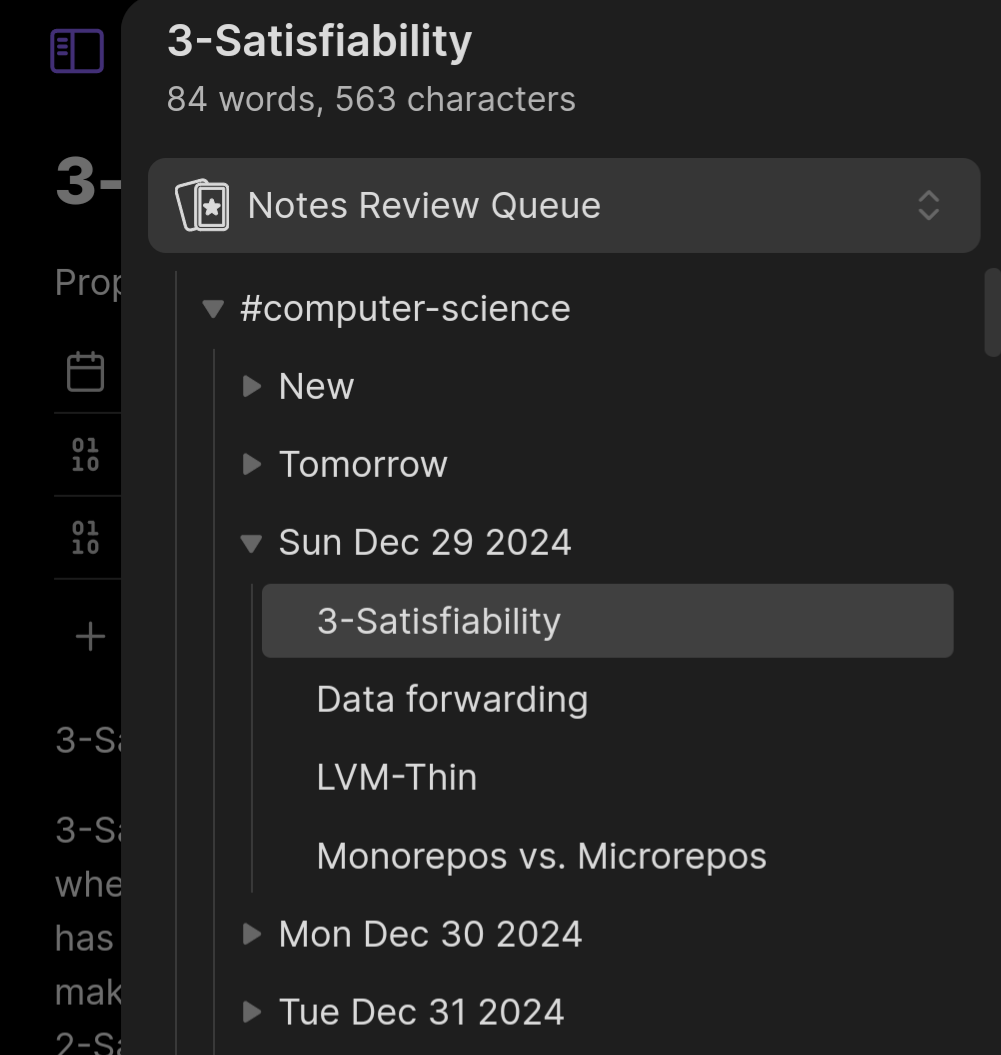

For every day I then have a list of notes to review.

Depending on "how good I did" I rank the notes as either easy, good or hard, which sets the next due date to either later or earlier.

Doing multiple repetitions of anything I learned sounded daunting at first and I must admit that it still is tedious sometimes. Additionally, it is tempting to start a new topic as soon as the previous one is completed, as it feels more rewarding. But I have found that spaced repetition is by far the most effective tool for persistent and sustainable knowledge increase.

First you actually remember what you just studied. I notice a great discrepancy in recall of things I just consumed and those I actively engaged with by doing a few rounds of spaced repetition. I often experience this when I discover a note I have no memory of, realizing I forgot to put in the spaced repetition loop.

But the most important aspect I see in spaced repetition is that everything, no matter if you remember it in your sleep, comes back at you. This way you can think about them with a new perspective maybe understanding them on a deeper level. Moving from a more abstract idea to a concrete example and back, see semantic wave. Or taking advantage of the things you have learned in-between to find new connection or detecting errors in your old reasoning. Additionally, it helps to tackle hard things. Quite often I write a note about a concept I do not fully grasp at the time. I no longer feel bad about this, but just drop perfectionism and add it to the loop, knowing that I will figure it out down the line.

Take on and seek out learning opportunities

Learning opportunities arise more often than you might think. The things that can have the biggest potential to increase your knowledge can sometimes be right in front of you. Take those opportunities on and seek them out.

The thing I find most stressful as an engineer is if something breaks, I don't know why, and I have to fix it quickly. I dread this combination of urgency and being out my comfort zone. Unfortunately in such situations I often find myself defaulting to inefficient problems solving techniques. Such as extreme loops of trial and error without reasoning and just using things I found online. I think I do this, because not fully grasping the issue at hand is uncomfortable and taking it slow to actually understand what is happening is challenging. Taking it slow can feel like no progress is being made. So I prefer the easy way of rapidly doing actions, while mostly inefficient, to the tougher challenge of actually facing and fixing my blind spots.

As such situations are not a rarity and arise more often than I wish, I have started to view them as learning experiences that I have to take on instead of simply fixing. I try to not panic and just solve them as fast as possible, but actually take my time to understand what is happening. This can lead to frustration and despair, but as mentioned before, while this is uncomfortable, it is often just a sign that learning is going on. I try to use those feelings as a guide and appreciate them. The first time I came across this idea was in Julia Evans' zine The Pocket Guide to Debugging, which I highly encourage you to check out.

Unfortunately this is far easier said than done, but what I have found most useful is to reduce the feeling of urgency as best as possible. Often, things feel far more urgent than they actually are, and being uncomfortable only enhances this. So when I feel the itch to fall back to inefficient fast action methods I do a reality check to figure out how much time I could actually spend on an issue. In other situations I seek out a quick and dirty solution to mitigate an issue and give myself time that I can spend in peace.

What I have found is that such situations, while uncomfortable, can serve as the best learning experiences and greatly enhance one's understanding. Additionally, I have found that I do not need to wait for things to actually crash. Often I can find such valuable experiences in the things I procrastinated on or in tasks that no one on the team wants to do. What helps me to find and take on such challenges is to reflecting on why I don't want to do them. Is it because they are tedious and boring, or am I actually just not confident enough to perform the required tasks? So, in short, if it is a skill issue, do the task and learn something.

Focus your effort

In learning, like (almost) everything else in life, focusing on concrete goals and making steady progress beats aimless sprints. You should learn with an action in mind: to apply the newfound knowledge or to follow some broader high-level goal.

Don't treat learning like some mindless consumption on an endlessly scrolling dopamine app. Don't hop from topic to topic without going deeper than surface level. I have often fallen to this trap and still do. While it is enjoyable for the sake of curiosity and broadens one's perspective, in the end, nothing really sticks, and the result feels hollow to me. To combat this, I use two approaches.

The first is that I follow one or more foundational, long-term goals, for example, teaching myself computer science. While I often cannot directly apply anything I learn here, the knowledge foundation I build helps me pick up things faster when I actually need them. It acts as a long-term investment where I am sure it will not quickly fall out of fashion, in contrast to some hyped flavor of the month.

The second approach is that I try to learn similarly to the Toyota way. Toyota only builds car parts when they are needed, so I try to only dig deeper into a topic when I want to actually apply it in the near future. While it can be tempting to experiment with a shiny new framework by skimming through documentation and completing tutorials. I have often found little value in it if I don't use it to solve real problems and gain practical experience with it. Therefore, I try to avoid getting sidetracked and focus on improving at the things I am actually using. For a deeper insight on this aspect see this great blog post.

This combination of building long-term fundamental knowledge and spiking in detailed areas that I encounter every day, has served me well. While it is still hard not to fall victim to FOMO, it feels great when I notice that I can pick up a new framework more quickly by leveraging knowledge of some underlying concept. Additionally, focusing on a few areas to gain an understanding beyond the advanced level not only tremendously helps with everyday work, but can also yield unexpected transferable skills.

Closing thoughts

Reflecting on the things I have written, I come to the conclusion that I now learn more systematically and consciously. I use systems to make hard challenges easier, and therefore feel more confident and secure tackling them. Also, due to repetition and reflection, I have become more aware of how I am thinking while learning. (a process I recently learned is called metacognition). This allows me to learn more efficiently and make it more enjoyable, so I continue to do it. Overall, I am quite happy with the progress I have made and hope that reading my experiences helps you reflect on the way you learn.